Livingston Montana Trout Food: Hatch Charts and Other Trout Prey for the Livingston, Montana Area

I have no idea how many different species of prey the trout, grayling, and whitefish around here feed upon. That said, there’s only a relative handful anglers need to imitate. This page includes information on the most common bugs anglers should be prepared to match region-wide.

Some critters not mentioned on this page can be important one one or two fisheries. These are discussed on the relevant pages in the Our Fisheries section of the website.

Baitfish, eggs, crustaceans, and worms are only important sporadically. Their imitations are discussed on the Flies Page.

Far better photos of trout stream insects than I can provide are found at Troutnut.com. This website is dedicated to scientifically-detailed discussions of aquatic insects, and includes pictures of both aquatic and airborne stages of pretty much every aquatic insect you can think of.

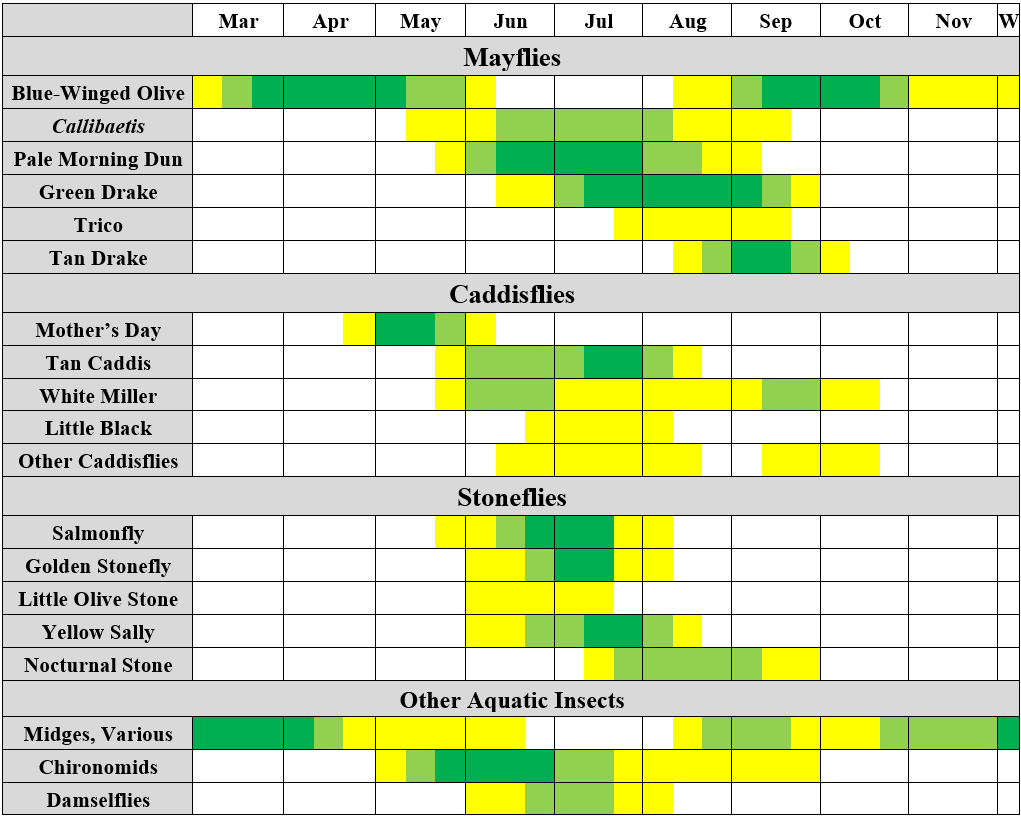

Livingston-Area Aquatic Insect Hatches and Montana Hatch Chart

Aquatic insect hatches are the only food sources anglers should be prepared to match specifically on almost all waters most or all season long. When hatches aren’t underway, area game fish tend to be more generalist in their feeding habits.

The number of aquatic insect species the trout eat can be really daunting. There are probably fifty different bugs I’ve seen trout feed on once in my time fishing the region. There’s no reason to prepare for all of these different bugs, since a lot of them actually look rather like other insects or won’t be found everywhere.

The following hatch chart is intended to keep things manageable. Odds are, if you come prepared to match the insects most likely to hatch during the time period you’ll be here, you’ll be close enough to any other minor hatch that’s underway, too.

Mayflies

Blue-winged Olives (BWO) are generally members of the Baetis genus. They are the most important and widespread mayflies in our area. They hatch from all streams and can be important on almost all. While you might see one or two in inclement summer days at high elevations, they are most important in spring and especially fall. Trickles may hatch from the Yellowstone River and Paradise Valley spring creeks even in the dead of winter. In April and autumn, most in our area run #18. In the winter, on Paradise Valley spring creeks, and on the Firehole and Madison in YNP, late fall BWO may run as small as #24, though you can usually get away with larger flies. As their name implies, these insects have gray-blue wings and at least some olive to the body. Fall insects in particular tend to appear almost straight gray. Good dry flies include Upbeat Baetis, Hi-Viz Gray Baetis Parachutes, Baetis Sparkle Duns, and even Parachute Adams and Purple Hazy Cripples. Good nymphs include Radiation Baetis, WD-40, Sunkist Baetis, Slim Shady Baetis, and Jujubaetis. CDC Emergers and Cripples are good for the in-between stages. BWO spinners are seldom important but are pale olive. BWO usually hatch in the afternoon, particularly from October through early spring. Even in September the strongest bug numbers are after lunch, though the hatch may start a bit earlier. They may hatch in the mornings in late spring, particularly on the Firehole.

Callibaetis are THE lake mayfly. While a few lakes have other mayflies, this is the critical one. They are gray in color (sometimes with hints of olive or tan) and #12–16 depending on the water (#14 most common). Most have prominent speckling at the leading edge of their wings, and they have two tails. Both duns and spinners can be important. Good duns include Callibaetis Cripples and Parachute Adams, while spinners should be dedicated Callibaetis spinners. Good Nymphs center on Rickard’s Stillwater Nymphs. Callibaetis hatch around midday except when it’s windy, when they don’t hatch at all.

Pale Morning Duns are the most important summer mayflies. They hatch on almost all waters, but are most important on flat, gentle streams. They may also be found in fishable numbers on isolated pools on larger rivers. They are seldom important on rough streams. These are pale yellow-gray insects ranging from #14 (early season, on the Firehole) to #22, with #16 and #18 most common. The larger bugs are actually a different species than the smaller ones, but they all have similar habits. The larger bugs hatch earlier in the year. Nymphs, emergers/cripples, duns, and spinners can all be important. Nymphs center on Slim Shady PMD and Split Case PMD. On larger waters Pheasant Tails are usually close enough. Emergers center on CDC and snowshoe rabbit-winged flies that are either 1/3 or 2/3 the color of the nymph, the remainder pale yellow with gray wings. Duns center on Sparkle Duns (with a bit of crossover to emergers), DOA Cripples (with obvious crossover to cripples), and Hairwing PMD (on rougher waters). Spinners should be rusty or pale olive. Duns hatch from midmorning through midafternoon most often, while spinners are out in late evening or early morning.

Green Drakes of genus Drunella and various species are the most important large mayflies in the area. They range in size from #10 down to #16, with #10 through #14 most important. The larger insects are probably D. doddsi, the smaller ones D. flavilinea or D. coloradensis. These are all robust gray mayflies with hints of yellow-olive. They are often called Gray Drakes, and Gray Drake imitations actually do a better job imitating them than the greener patterns favored elsewhere. Rest assured, despite the color differences, these are indeed Green Drakes. In terms of habits, habitat, etc. they behave exactly like other Green Drakes. Gray Drakes are silt-dwelling swimming mayflies. Green Drakes live in faster, gravel-bottomed water. We do see a few of the robust greener bugs, particularly on the Yellowstone River in July and in the Lamar System in September. While Green Drakes can hatch from all gravel or cobble-bottomed streams, they are most common in the Lamar System, where they are definitely the most important hatch overall. Look for hatches from mid-morning until early afternoon in July and August and later in the day in September. Good duns include Furimsky’s Gray Foam Drake, Keltner’s Soda Fountain Parachute, and on remote streams even large Parachute Adams or other attractors. My favorite emerger is the Gray CDC Emerging Dun. Nymphs and spinners are seldom important.

Tricos (Tricorythodes): Are tiny black or pale gray-bodied (males and females are different) mayflies with clear wings. They are only important on slow water and usually only in scattered spots. While the trout can get very selective towards these on other waters in Montana, most especially the Missouri River, in our area it’s usually possible to get away with small attractor dries or even ant imitations which the trout are also eating in the same timeframe. If you see slow, delicate rises in slow water on August or September mornings, odds are they’re eating Trico spinners or perhaps midges. Tiny Purple Hazy Cripples and Mercer’s Missing Links are about as close as we get around here as far as imitation.

Tan Drakes: aka Drake Mackerals aka Fall Drakes aka (probably) Timpanoga hecuba aka Hecubas take over from Green Drakes in late August and September. They are #12–14 and tan, with prominent rusty brown ribbing. They are most common in the Lamar System but can pop from time to time on the Yellowstone River as well. It seems like one great year for these on the Yellowstone comes after two or three poor ones. They often hatch in conjunction with afternoon BWO, so fishing a big tan dry with your tiny olive-gray one as a dropper makes sense. Dedicated patterns work best in the Lamar System. March Brown Sparkle Duns actually look just right. Elsewhere, more robust flies such as the Brindle Chute and Brindle Cripple work just as well and float better. Spinners are rusty-tan, but seldom important.

Caddisflies

Mother’s Day Caddis: genus Brachcentrus, are the region’s second-most-fabled hatch and the hardest to hit right. They hatch on the Yellowstone River in early May right at the onset of spring runoff. At least half the time, the hatch is completely blown out by the melt and unfishable. The Lower Madison’s hatch in the second half of May is not quite so spectacular, but much more consistent. The Firehole, Madison, and Gibbon see a few in early June, though these seldom need to be imitated since there are other bugs around in greater numbers. Mother’s Day Caddis are #14–16, the former more common on the Yellowstone and Firehole, the latter more common on the Madison. Adults have olive to olive-brown bodies and gray to gray-brown to brown-tan wings. Pupae have olive or chartreuse abdomens and dark heads. Both can be very important, as can olive-bodied emergers and cripples. They are most important in afternoon, but fishing a pupa behind a streamer or attractor dry is always a good bet. While olive-bodied X-Caddis are a good imitative dry, I tend to use my Clacka Caddis with a peacock body. Even small Coachman Trudes can work, especially when the hatches are especially heavy and the trout are going wild. The best pupa is a green Kryptonite Caddis. The best emerger is a green McCue Pupa.

Tan Caddis genus Hydropsyche, are the dominant summer caddis and probably the most widespread summer aquatic insect overall. They hatch from all streams, and are #14–16, with the emphasis on the latter. That said, they need to be matched with precise imitations very seldom, especially on the surface. Even during heavy hatches on gentle streams like the Lamar River, it’s common for the fish to take robust attractor dries as well as imitative flies. If you do imitate the adults, fish tan X-Caddis or tan Caddis Cripples. Peacock or even pink (really) Clacka Caddis often work just as well, and if you’re fishing near dusk don’t hesitate to fish a #12–14 Coachman Trude with an imitative fly behind it. Another good option is to match pupae or emergers behind an attractor. The pupae are dark tan to amber. Kryptonite Caddis, tan Fuzz Bastards, or Bird of Prey Caddis work well, as does the Gut Instinct. Emergers should be tan Partridge Caddis Emergers.

White Miller Caddis: aka Necopsyche are the most important hatch of all on the Firehole River and are also found in small numbers on the lower Gibbon and Madison Rivers. They are seldom important except on the Firehole. They hatch there from the beginning of the season, hatch in clouds in June, and last until sometime in October. Fish White Miller Soft Hackles on the swing to cover the pupa. Fish White Miller Caddis Cripples or Palmered CDC & Elk to cover adults. All these flies should be tied on #14 short-shank hooks.

Little Black Caddis aka Glossossoma are exactly what they sound like. These #18–22 caddis hatch in vast swarms in late July. Thankfully, they almost never need to be matched on our waters (portions of the Madison River beyond day-trip range from Gardiner are a different story). In the rare instances you do see fish hitting them, fish tiny tiny black Henryville or similar old-timey caddis.

Other Caddisflies tend to hatch in small flurries unpredictably during the summer months. Most are small and tan or amber colored. There are three main exceptions. A #10 2xl chocolate caddis hatches with the Salmonflies in early July. Match it with a #10 Synth Double Wing or Coachman Trude. The October Caddis is far more common further west, but we see a few in late September and early October. This fly does not need to be imitated on the surface. Large orange or amber-bodied pupae work well for fall-run browns in particular. The Traveling Sedge is the only common lake caddisfly. Even on lakes it is not common. Trout Lake sees the best emergences. Look for vee-wakes cutting under the water. These are emerging pupae. Unweighted Muddler Minnows actually imitate these bugs. #10 natural Letort Hoppers can also be stripped wet, or can be fished dry in the rare instances you see fish actually eating these flies on top rather than just underneath.

Stoneflies

Salmonflies or Giant Black Stoneflies (Pteronarcys californica) are the largest aquatic insects in the region that hatch in any numbers. Their hatches on many Western rivers are fabled. They hatch in epic numbers on the Yellowstone in the Black and Grand Canyons and downstream from Gardiner about 20 miles. They hatch in smaller numbers further upstream and down on the Yellowstone and in rough sections of all other rivers (as opposed to creeks) in the area. Fabled hatches are also found on the Madison and many other rivers beyond day-trip range of Gardiner throughout the West. These are dark gray to black and orange insects. Flies (both nymph and dry) should be #4–6. Most imitations have too much bright orange, when the bugs themselves have more brick orange. The nymphs are dark brown until immediately before emergence, when they gain orange undersides. Both stages are critical. Fish black or dark brown stonefly nymphs almost anytime, but especially in the month before runoff on the Yellowstone and immediately as runoff begins to recede on any rough rivers. Add flies with orange undersides like the Bitch Creek a few days later. Fish the latter tight to shore, as the fish pursue the emergence migration towards bankside rocks and bushes. Adults combine soot gray or black with orange. Both “fur and feather” traditional patterns like the Improved Sofa Pillow and Orange Stimulator and foam patterns work well. There are innumerable foam flies on the market. Select those that float low and aren’t too bright; the fish see too many large, bright orange bugs. Hatches relate to water temperatures. They hatch as the season begins and in early June on the Firehole, in mid-June on the Madison in YNP and Lower Gibbon, and from late June through July on the Gardner, Yellowstone, and Lamar. Peak hatches are on the Gardner and Yellowstone in early to mid-July.

Golden Stoneflies (mostly Hesperoperla pacifica, some Calineuria californica) hatch at the same time or just slightly after the Salmonflies, usually in somewhat lower numbers. They are found in even more places, with a few even in places like Soda Butte Creek and lots in the Gibbon and further afield on the Boulder Rivers. Use similar flies and tactics as when matching Salmonflies, but size down to #8–12 and switch colors to golden yellow, sort of an “antique gold” is best, with prominent darker barring or speckling. Impressionistic Golden Stonefly nymphs are better all-purpose flies all season than Salmonfly nymphs, since these golden-brown flies also look like sculpins and large caddis pupae.

Little Olive Stoneflies of an unknown species hatch in fishable numbers on the Gibbon River and Slough Creek. These are #14–16, smaller than the Skwalla stoneflies more common further west. Montana Princes (a Prince with an olive green wire body) match the nymphs, while Olive Stimulators or even Coachman Trudes match the dries. They are only around for a week or two in June on the Gibbon and July on Slough, but the fish do seem to like them.

Yellow Sallies (genus Isoperla) are the most common stoneflies overall. They are found on virtually all flowing waters except spring creeks and areas with silt bottoms, including meadow waters like Soda Butte Creek. While dry Yellow Sally imitations are popular (Yellow Stimulators, Goldie Hawns), and airborne yellow stoneflies that look like gray-winged biplanes or helicopters (many with pink to red abdomens and egg sacks) are common sights, the nymphs are much more important to the angler. By far the best right now is the Montana Jig Sally, a jig-tied and tweaked version of an earlier pattern called the Iron Sally. This is one of the better nymphs to fish in July on any rough water, especially on Yellowstone River floats. Yellow Sallies are #14–16, heavier on the latter.

Nocturnal Stoneflies aka “Midnight Stones,” Claassenia sabulosa, are sometimes called “late summer Golden Stoneflies.” As the name suggests, these large tan/black stoneflies hatch at night. The most common sign of them by day are nymphal shucks left on bankside rocks in the morning. You’ll see one or two here, one or two there, rather than vast numbers as you can of Salmonfly and Golden Stonefly shucks. The smaller male adults do not fly (these insects are also called “Shortwing Stones” for this reason), but sometimes skitter across the water. Once in a while you’ll see a #6 or #8 female flying by day. Unlike Salmonflies and Golden Stoneflies, these insects have a prolonged emergence. They start in July but can last into September on rivers with large populations, such as the Stillwater and portions of the Yellowstone east of Livingston. Near Gardiner they are most important on the Yellowstone and Gardner, but may show up in the Lamar Canyon as well. Nymphs work best. Tan/black or tan/brown Girdle Bugs and TJ Hookers in #8–10 are most effective, and the 20-Incher may also suggest this insect. On the surface, one thing the ultra-popular Chubby Chernobyl (and older Turck’s Tarantula) imitates is this fly, especially when tied in gold or tan/black. Many hopper patterns also look a lot like this fly, which goes a long way to explaining why large tan hoppers are effective in early august when the hoppers are mostly still smaller and paler. All dries should be #6–10, which is one reason huge Chubbies supporting large nymphs is probably the most popular “guide rig” on Yellowstone River float trips.

Other Aquatic Insects

Midges are certainly the most common insects in the region, but they aren’t as important from a fishing perspective as they are in many other places. In general, the lower, colder, and clearer the water, the more likely the trout will be eating midges in rivers and streams. This makes late fall through April the most likely time to see trout rising to midges. On the spring creeks, midges are also one of the main food sources from mid-May through mid-June and again in August and September when few mayflies are hatching. There are also midges popping in the Lamar System beginning in late August. On lakes, both relatively small (#18) and large (#12–16, aka chironomid) midges are important food sources. The trout might take midge larvae and pupae on lakes at any time, but midge hatches are most common from May through July, and are most important when few larger mayflies or damselflies mix in. On streams, small, sparse flies consisting of little more than thread and a rib are usually best at imitating subsurface midges. Zebra Midges in classic black and silver as well as black and copper are my favorites. These should be #18–22. On the surface, either Parachute Midges, CDC Biot Midges, or midge cluster patterns like #18 Griffith’s Gnat are best. I usually combine these with a slightly larger attractor dry to serve as a strike indicator. On lakes, larger versions of the same flies work on the surface, while I like Driscoll’s Midge and BLM nymphs underneath.

Damselflies are occasionally found in slow-moving, weedy sections of fertile streams like the Firehole and the Paradise Valley spring creeks, but they’re much more common in lakes. While small numbers hatch as early as late May, the main action is from mid-late June on private lakes and late June through July on lakes in Yellowstone Park. Damselfly hatches get the trout very excited. Strip the nymphs towards shore on stout tippets (hard strikes). I like Stalcup’s Damsel in #12. When the trout start rising hard, especially coming out of the water, fish Foam Blue Damsels in #12–14.

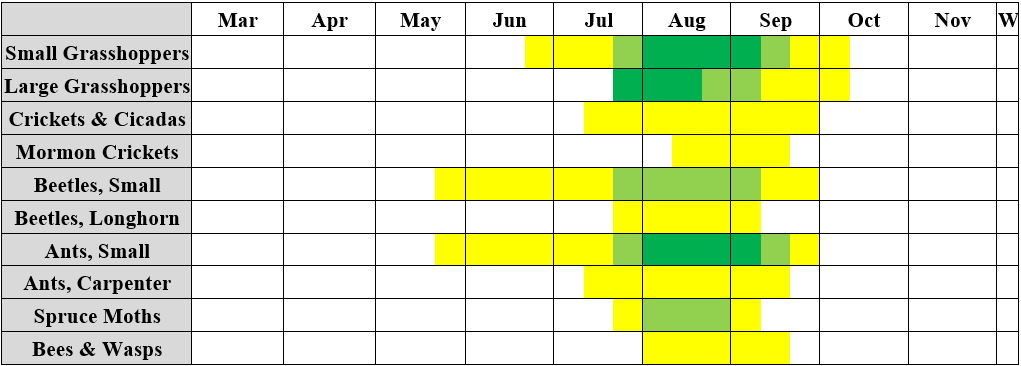

Terrestrial Insects

Terrestrial insects that jump or fall in the water, or are blown there, are vitally important flies in late summer and early fall when hatches may be limited. They’re also a lot of fun to fish, since trout seem to take them with extra gusto.

Note that the “small grasshopper” effectiveness prior to mid-July is limited to ranch lakes and the ant/beetle effectiveness prior to mid-July is limited to spring creeks. Otherwise, terrestrials turn on as aquatic insect activity turns off. They remain good until the first hard frosts (or especially snowfall) in late September.

Small Grasshoppers: Small grasshoppers are those size 10 1xl or size 12 2XL or 3XL and smaller. For numbers of trout and almost all fishing on smaller streams, these are usually more effective than big ones, though many can’t support the weight of a dropper nymph. My favorite in this category is unquestionably my Bob Hopper, though many “fur and feather” traditional patterns like Parachute Hoppers are also popular. By all means experiment with colors here. While real small grasshoppers tend to be pale green, yellow, or tan, with dark-barred kicker legs, the trout will eat all sorts of colors. Peach or flesh foam, mustard-yellow foam over a brown underbody, bright pink… you name it.

Large Grasshoppers are #8 1xl or larger, or more commonly #10 2XL and larger. The largest hoppers regularly effective are #6 3XL, with #10 3XL certainly more consistent. These flies may be Chubby Chernobyls, but Yeti Hoppers, Morrish Hoppers, or the local Sweetgrass Hopper are much more popular and productive in this role. These flies can and usually do float large nymph droppers. They’re typically most effective in shades from cream to dark tan, which imitates natural hoppers as well as Midnight Stones, but in years with high hopper populations brighter or more ostentatious hoppers in pink, peach, flaming yellow, etc. might work as well. They are most effective on large rivers (like the Yellowstone) when you’re looking for a couple big fish; they’re usually only effective for numbers of trout in remote sections of big water. The fish are a bit too skittish where there’s a lot of pressure.

Crickets & Cicadas, which I’m defining as anything relatively large (#8–12) and dark-colored are either completely ineffective or extremely productive. It seems to depend on the year. Some years there’s a strong bite in July, some years not until September. When these flies are on, my favorites are Card’s Cicadas in the appropriate size.

Mormon Crickets are actually flightless katydids. These almost greasy-looking, fat, and imposing bugs are most common on the Gardner, Yellowstone, and Lamar in late August and early September. They are #6–8, 3xl and very fat. This makes them tough to imitate, especially on the Gardner where most trout are really too small to eat them. Fish #8–10 tan Fat Alberts.

Small Beetles can interest trout on the spring creeks in May, but they are most useful in late summer on meadow streams. These should be black with peacock bodies and #18. If you can’t figure out which small aquatic insect the trout are taking, sometimes they’ll eat a beetle. I always use #18 black foam beetles without legs, but some people like complicated flies.

Longhorn Beetles are #12, 2xl, and have long antennae. They are most common in the Lamar System. A dedicated pattern by Blue Ribbon Flies is the only bug I use to match this insect, and it’s strictly a “changeup.”

Small Ants: are usually more important than beetles, and in low water years they are often much more effective than grasshoppers. Both flying and flightless ants are possible. The former are #18–20 and black with transparent wings (they look like midges) they are most common in the Lamar System in late August and early September. Flightless ants are either red and black (some with red heads and black abdomens, some vice versa) or cinnamon in color. In the Lamar System, either traditional fur ants without any kind of wing or post or low-floating parachute ants are best. On rougher water, especially the Yellowstone, I like flying ants with synthetic wings and heavy hackle. On the Yellowstone in particularly I think this pattern crosses over with mayfly spinners, midges, and caddisflies that may be present in small numbers at the same time. These ants are all #16–18.

Carpenter Ants, really any ants larger than #16, are most useful as general attractors in rough water. I fish assorted hairwing ants (mostly cinnamon ones) in #12 and #14. Galloup’s Ant Acid or Turck’s Power Ant are good choices. These flies should generally have legs and/or heavy hackle. They tend to work best when the trout are really on ants. I’ll often fish one of these with a small one on the dropper.

Spruce Moths, really Spruce Budworm Moths, are an evergreen tree parasite. As such, they are only important near evergreens. They look like cream caddis, but are actually small creamy tan moths. The most important places in the region for these bugs are the Gallatin River outside of day trip range (both inside YNP and in the Gallatin River Canyon) and upper Soda Butte Creek. That said, when infestations of these flies are heavy, anywhere with evergreen trees can produce on imitations. I do mean anywhere. I once had a great morning right through Livingston on the Yellowstone River just because of all the decorative evergreens in yards, and also had a good day in Yankee Jim Canyon due to the sparse lodgepole pines and junipers. Fish #14 Parachute Spruce Moths, my Widow Moth or Doug Korn’s Spent Wing Spruce Moth. These bugs are most common in August.

Bees and Wasps sometimes excite the trout in late August and September in the Lamar System when they’ve seen too many other terrestrials. I’ve never caught a fish on one otherwise. Fish #14 foam bees.