Native cutthroats, beautiful (but hard) hikes, and limited angling competition... The Yellowstone River in Yellowstone Park is our favorite hike-in river.

The Yellowstone River in Yellowstone Park is almost as large as it is downstream in Montana, but fishing the Yellowstone River in Yellowstone National Park is almost completely different than in Montana.

Stretches near Yellowstone Lake are slow, broad and home seasonally to a few huge cutthroat. Downstream of the famous Upper and Lower Falls, the river leaps into one of America’s deepest canyons, the Grand Canyon of the Yellowstone. In some places canyon walls rise 1500 feet almost vertically from the river. Through this canyon and the next, the Black Canyon of the Yellowstone, the Yellowstone runs, fast, deep, and brawling. It’s also a wilderness river in these canyons, with a grand total of one road bridge over the entire distance. This makes the Yellowstone in its canyons probably the best river for avid hikers in the entire region.

We guide more on the Yellowstone River in Yellowstone Park than we do on any other water inside the park boundaries. There’s no legal floating in Yellowstone Park, so the river is walk & wade (really hike & wade) only here. If you’re an eager hiker not afraid of tough hikes, steep banks, fast water, and boulders in exchange for good numbers of chunky native cutthroat trout, the Yellowstone in the park is a great wade-access river.

The Yellowstone River is ideal for anglers who are up for a hike.

Note that this page covers only the portion of the Yellowstone downstream from Yellowstone Lake. The “Thorofare” region upstream (south) of Yellowstone Lake, in the southeast corner of the park and even on into northwest Wyoming, requires a multiday backpacking or horseback trip to reach, so neither Yellowstone Country Fly Fishing nor Livingston itself are good resources. Fishing tactics will remain similar to those noted here for the Lake to Falls stretch.

- Learn about our walk & wade guided trips, for which the Yellowstone in the Park is our favorite destination in July and August (and pretty good in September, too).

- Yellowstone Lake Outlet Stream Gauge: As long as flows aren’t steadily rising here (most common in June), the Lake to Falls and Grand Canyon are usually clear and fish well (season permitting).

- Lamar River Stream Gauge: Sudden spikes on this gauge probably mean the Black Canyon of the Yellowstone will be too muddy to fish.

Yellowstone River in Yellowstone Park – Description & Access

Fishing the Yellowstone River in Yellowstone National Park is basically the “tale of three rivers.”

The headwaters upstream from Yellowstone Lake in the Thorofare are pure wilderness days from the closest road. Only serious backpackers need apply. As noted above, we won’t discuss this stretch further

Near Yellowstone Lake, the river is broad but often easy to wade, flowing in a mix of meadow and woodland. It’s impossible to cross in most spots, but the Canyon–Lake Road follows the river at a distance of less than a mile (and often a few feet) on the west side and a flat, well-traveled trail follows the east side. Here the river is either in a single broad channel or splits into smaller channels around gravel bars and islands, each of which usually has an attractive riffle and pool associated with it. Only one large rapid breaks up the relatively serene (though powerful) flow. Otherwise it’s riffles and pools. Hot springs line the banks here and there, and bison and bear encounters are common.

Then the river jumps over Upper and Lower Falls and flows in a treacherous canyon for its entire remaining run in the Park. Here the river is almost entirely away from roads, requiring always-steep and often-long hikes to access. The river is a mix of turbulent rapids and heavy runs, with very few places it’s wise to wade deeper than your knees and many where even that is impossible. Large boulders, steep banks, and a fair number of bears complete the wilderness ensemble.

Except for one section that’s adjacent to a road bridge, all of this water requires a hike to access, and many of the hikes will be beyond older anglers. Hot springs are pretty common on this stretch of river as well, though most of them are tiny enough they hardly even puff any steam, and animal encounters are somewhat less common (except for the trout).

Fishing the Yellowstone River in Yellowstone National Park

The Yellowstone River offers two very different characters suitable for very different anglers. Near Yellowstone Lake, the river is an “experts only” affair, but pretty easy to access with a road parallel to one side and a flat hiking trail on the other side. The potential for bison encounters is the only real potential problem.

In the canyons, the Yellowstone is suitable for anglers of all skill levels, even beginners with a guide or experienced angler to teach them what’s what. It is very difficult to access, however. Even when the hikes are short (in some cases less than a mile), the banks are steep and crumbly, the boulders large and slick, and the wading often treacherous.

Fish Populations

- Yellowstone Cutthroat dominate the fish populations. Upstream of Lower Falls, they are in effect the only gamefish. They still make up the vast majority of the trout population even within sight of the park boundary just outside Gardiner. The trout upstream from Chittenden Bridge are primarily lake-run fish from Yellowstone Lake. They average 16–22 inches and get larger. The fish downstream in the canyons are resident and are far more numerous but smaller on average. They run either 8–16 inches or 10–18 inches depending on the year and the specific section involved. In general, areas that seem to hold lots of fish hold fewer big ones.

- Rainbow and Rainbow-Cutthroat Hybrid join near Tower Falls. They must all be killed upstream of Knowles Falls in the Lower Black Canyon. Rainbows average 10 inches. Hybrids sometimes reach 24 inches but average similarly to cutthroats.

- Mountain Whitefish gradually show up between Hellroaring and Blacktail Creeks in the central Black Canyon but are far more numerous downstream of Knowles Falls. They average 8–16 inches.

- Brook Trout are uncommon everywhere but may be found near the mouths of tributaries that hold them (Tower and Blacktail Creeks in particular). Most are hand-size, but I once caught a 16-incher two miles upstream from Gardiner.

- Brown Trout are found downstream of Knowles Falls, but always make up a small minority of the trout populations.

- Lake Trout were introduced illegally to Yellowstone Lake in the 1970s and have decimated the cutthroat populations there. It’s conceivable but very unlikely you might find one in the river near the lake. All lake trout must be killed.

- Smallmouth Bass are exceptionally unlikely, but one was caught a couple years ago adjacent to the park boundary in Gardiner. It was probably illegally stocked. All smallmouth bass caught must be killed and reported to the Park Service.

Fishing the Yellowstone River in Yellowstone National Park centers on native Yellowstone cutthroat trout.

Fishing Season – When It’s Open and When It’s Good

Downstream of the falls-area closure zone (Chittenden Bridge to Silver Cord Cascade), fishing the Yellowstone River in Yellowstone National Park opens with the park’s general season on the Saturday of Memorial Day Weekend. The Grand Canyon is often fishable for a few days right after the opener if spring has been cold. It is phenomenal at this time if you can hit it. The Black Canyon is almost never fishable at the opener, and except in extreme low water years, the Grand Canyon also goes into runoff shortly after the opener. The Grand Canyon usually becomes fishable again between June 15 and July 1. The Black Canyon becomes fishable between June 20 and July 15, with the first week of July most common.

Both canyons fish best from when they drop into shape in late June or early July through August, but both remain fishable through the end of the park season on Halloween. The Grand Canyon is usually much more consistent in the fall.

The Yellowstone upstream from Yellowstone Lake and from the lake to Chittenden Bridge near Upper Falls now open July 1. The longtime opener was July 15. We suggest avoiding this water before July 15 to protect spawning trout. Why the Park Service started opening this water two weeks early when the whole point of the late opener was to protect the spawn (which sometimes isn’t finished even on the 15th) is beyond us. The fishing is always best for the first month after July 15, then fades as the big spawners move back to Yellowstone Lake.

Note that many short sections of the Yellowstone River are permanently closed to fishing, particularly between Yellowstone Lake and the Falls and in the upper end of the Grand Canyon (which is impossible to access anyway). Some of these closures are several miles long, some much shorter. Please familiarize yourself with these closures by reading the park regulations prior to fishing the region.

Season Highlights

- Early Season Nymph and Streamer Fishing in the Grand Canyon: This fishing is seldom available, only about one year in three, but when the Grand Canyon is clear and fishable in early June, it’s possible to put up some huge numbers of fish in this stretch.

- “Opening Day” near Nez Perce Ford: I put opening day in quotes because they changed opening day from July 15 to July 1. Nonetheless, I suggest waiting until July 15 to let the cutthroats finish spawning. While high fish numbers are no longer possible in this stretch (as they were before the late 1990s), a few BIG trout are possible.

- Salmonfly and Golden Stonefly Hatches in the Canyons: The canyons see the best large stonefly hatches of any body of water in the country, including the Yellowstone downstream in Montana. The hatches last a long time due to the competing influences of hot springs, Yellowstone Lake, and cold tributaries. I once caught fish on adult Salmonfly imitations a month apart at exactly the same spot. Moreover, the difficulty of accessing this water means the fish seldom get wise to fake “big bugs.”

- Fall Streamer Fishing in the Grand and Upper Black Canyon: One September I set one client up on a good run with a couple streamers, then took the other client to the next run. By the time I got back to the first client 15 minutes later, he had already caught nine fish. Need I say more?

- Fall BWO Hatches in the Canyons: Some of the most productive Blue-winged Olive hatches in the region occur on rainy/snowy September afternoons in the canyons. You’ll often find pods of several dozen trout rising in good runs. No hatch? Throw streamers instead.

The Salmonfly hatch in late June and July offers chances to fish dry flies as big as your pinkie finger.

Yellowstone River in Yellowstone Park Fishing Tactics

Very different tactics are required in the canyons and near Yellowstone Lake. This is due to different fish populations (a few big fish near the lake, lots of midsize fish in the canyons), different water character (canyon vs riffle-pool), and different prey bases.

Near Yellowstone Lake, it’s almost always best to sight-fish when you can. This is easiest under bright skies with calm wind if there’s no hatch, while if the trout are rising, simply look for riseforms. Either way it’s best to cover lots of water looking for trout, rather than blind-fishing the structure. If you are blind-fishing, either swing streamers to cover as much water as possible or fish the most obvious juicy current seams in fast, turbulent stretches. Except near LeHardy Rapids, it’s best to fish relatively slender attractor or imitative nymphs and dries, whereas near LeHardy the trout are more likely to eat larger stoneflies and the like. Big nymphs and dries almost never work between Yellowstone Lake and LeHardy, since most prey insects in this stretch are small.

In the canyons, big subsurface flies (stonefly nymphs and streamers) can work all season long. Early and late in the year they are almost always your best bets. High summer and early fall are the only periods when slender attractor or mayfly nymphs (Copper John, Perdigon, Flashback Pheasant Tail) are almost always better than large wet flies. In June and after mid-September, expect to fish two nymphs under an indicator (or even a streamer dead-drifted under an indicator). In high summer and early fall, go dry-dropper even if you aren’t seeing rising trout, but be prepared to strip streamers.

Hatches in the canyons are limited and can usually be matched with attractor dries in the right size and silhouette. Only the fall BWO hatches result in lots of concentrated risers that might get picky. Otherwise you’ll usually find only a handful of trout fixating on any one thing. Even most rises to Salmonflies and Golden Stoneflies are opportunistic.

Except when fishing heavy hatches, it’s almost always best to fish the structure in the canyons. In the early season (anytime before mid-July), the trout tend to cluster in large eddies and boulder fields near the shore. Anything in the middle of the river is too fast. Later in the summer and in fall, they may move into offshore boulder fields and runs below riffles, but the bankside eddies remain good bets if the water in the middle is still deep and fast, as in most of the “tight” spots in the canyons. It’s almost never worthwhile to fish fast, deep water in the middle of the river, even with streamers. Cover lots of water when moving from spot to spot. There are large areas of dead water in much of the canyons, but the fish will be clustered in huge numbers in the good places, especially in the early and late season but even in high summer.

Insect Hatches & Other Prey

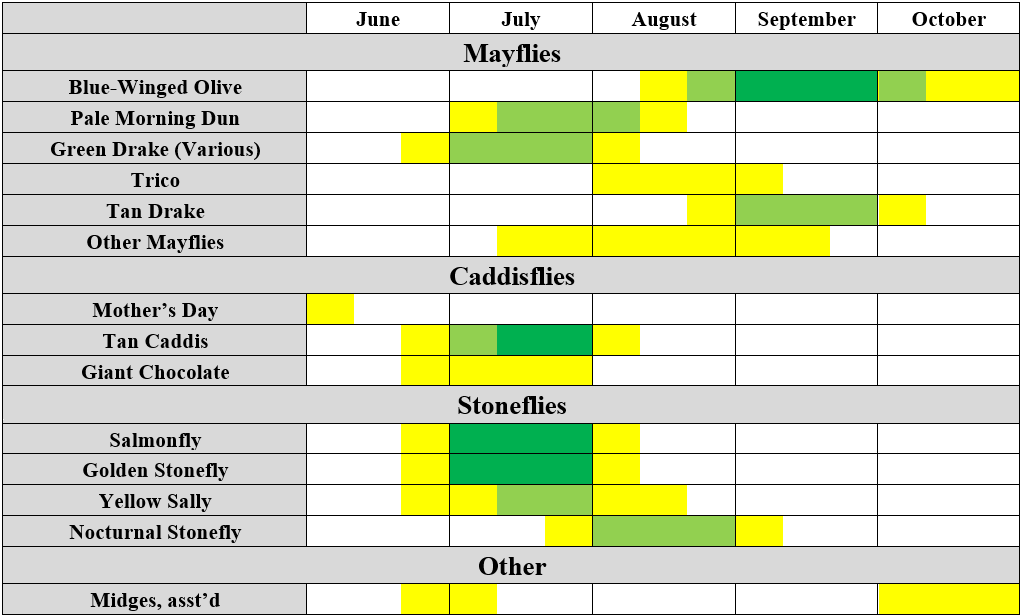

The following table provides info on important insect hatches for the Yellowstone in Montana. Matching hatches other than Salmonflies and Golden Stoneflies is seldom necessary in the canyons except in the autumn. Even when it is necessary to get specific, heavy hatches tend to be limited in area. You’ll find trout rising to PMD in one pool the size of your living room and nowhere else. Except in these circumstances, attractor dry flies usually work better.

Matching hatches is much more important upstream of Chittenden Bridge near Yellowstone Lake. Here Yellowstone River hatches are much heavier and the currents slower, so the trout can afford to get picky.

For information on insects and other food sources noted here, visit the Trout Prey page.

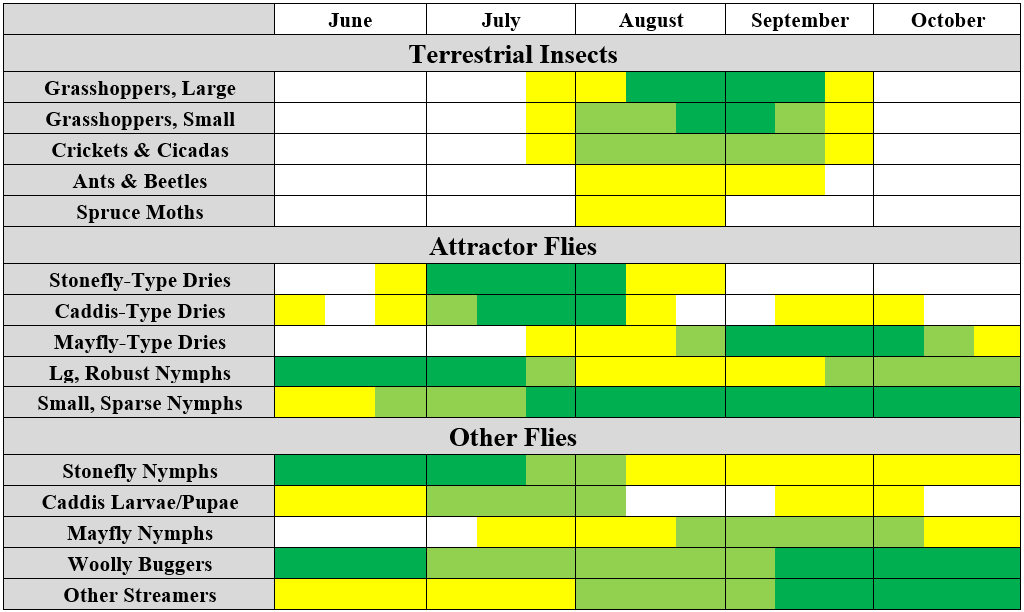

The next table provides info on other important trout foods and flies, ranging from baitfish to attractor dry flies. Streamers are probably the most consistent flies on the Yellowstone in YNP overall, particularly in the Grand Canyon, upper Black Canyon, and downstream of Yellowstone Lake after August 1. Terrestrial dries and larger attractor dries and nymphs work much better in the canyons than near the lake, though they can work in rougher areas downstream of the lake, as well. For info on fly patterns and types of flies noted in this table, visit the Fly Suggestions page.

Top 10 Flies for the Yellowstone River in Yellowstone Park

- Minch’s Golden Stone, #8–12

- Minch’s Black Stone, #4–6

- Olive Conehead Woolly Bugger, #4–6

- Minch’s Chocolate Bully Bugger, #10–12

- Purple Hazy Cripple, #16

- Tunghead 20-Incher, #10–12

- BH Flashback Pheasant Tail, #16

- Peacock Clacka Caddis, #12–16

- Beadhead Prince, #12–16

- Gold Chubby Chernobyl, #10

Large Woolly Buggers are almost always good choices in the canyons.

Sections of the Yellowstone River in Yellowstone Park

Besides the Thorofare stretch, the Yellowstone can be divided into three sections in terms of fishing tactics, water character, and accessibility.

Yellowstone Lake to Chittenden Bridge

The section of the Yellowstone between Yellowstone Lake and Chittenden Bridge at the head of the Grand Canyon closure zone was formerly one of the world’s great trout fisheries. It was famous for producing vast numbers of solid (though seldom huge) cutthroat trout, particularly for the few weeks following the traditional July 15 opener, which had a holiday atmosphere and vast crowds of anglers. Reputable anglers I know report catching as many as 100 trout per day here in late July during the glory days. Strangely enough, the glory days aren’t some far-distant past found only in grainy black and white photos, but the late 1980s and early 1990s. Restrictive tackle regulations and bag limits imposed in the late 1970s caused a population explosion at this time. Almost all of the fish were (and are) migrants from Yellowstone Lake. They descend from the lake following ice-out on the lake, spawn, hang out for the summer feasting on the abundant insect prey in this section of river, and gradually work their way back to the lake during late summer and fall to sit out the winter in the cozier lake instead of the shallow and ice-bound and snow-bound river.

Unfortunately, the illegal lake trout introduction in the 1970s reached a head in the mid-1990s when populations of these predators exploded. Combined with the onset of whirling disease and awful drought from the late 1990s through 2007, cutthroat populations collapsed. By some estimates, cutthroat numbers fell 97% in the lake by roughly 2010. No cutts in the lake, no cutts in the river. This collapse made the Yellowstone functionally unfishable from both productivity and ethics standpoints for around a decade.

Aggressive lake trout suppression efforts and several better water years to aid spawning (2008–2011, 2014, 2017–2019, and 2023) have led cutthroat populations to resurge somewhat. Instead of numbers down 97%, they’re down 80% or so from historic peaks. That’s still a far cry from the old days, but it means the Yellowstone downstream of the lake (and the lake itself) are now worthwhile and ethical fisheries again.

Lake-run Yellowstone cutthroat caught near Nez Perce Ford

They are very different than they used to be, however. Simply put, there aren’t enough fish to “fish the structure” effectively except with streamers. Swinging streamers is a very popular tactic here, even with switch and spey rods. The best tactic otherwise is to creep the banks on calm days with bright sun and to sight-fish for spotted trout. Nymphs produce better than dries, but rising trout are also possible during the prolific hatches that occur here. It is very rare for any angler to catch more than a handful of fish here in a day, but even one fish makes for a memorable day: a very high percentage of the trout here are large, with many over 20 inches and fat. The trout top out at probably 26 inches, and fish in the 24-inch class are taken at least weekly, if not daily.

If the above sounds like “New Zealand-style” fishing, that’s because it’s about as close to that sort of low-population, high-size “hunting” as you can get in the United States.

Insect populations are very different on this stretch than downstream in the canyon. Many species of mayflies, caddisflies, and stoneflies hatch here. PMD, Green Drakes, and Tan Caddis are most important, but there’s probably a wider range of prolific insect hatches here than anywhere else in the park. That said, fly choice need not be overly complicated—the problem is finding fish, not getting them to eat after you find them. I tend to carry a couple patterns to roughly match all of the insects of a different class. Sparkle Duns and Parachute PMD to match all light-colored mayflies, Parachute Adams or Soda Fountain Parachute to match darker mayflies, Caddis Cripples in tan, pink, and peacock to match all caddis, etc. Basic attractor nymphs like Pheasant Tails, Copper Johns, and Girdle Bugs work when nymphing, and streamers slant towards large Woolly Buggers.

This stretch of river can be divided into three rough sections in its own right:

- “The Estuary” runs from Yellowstone Lake to LeHardy Rapids. It is slow, glassy water best fished with swung streamers or when rising trout are spotted. Fishing is closed within a mile of Yellowstone Lake and at the rapids.

- LeHardy Rapids to Hayden Valley runs from the downstream end of the rapids to a point adjacent to Sulphur Cauldron (a major hot spring on the west side of the river). This includes the famous “Buffalo Ford” (now Nez Perce Ford) area. This stretch is faster, more turbulent, and more varied than the stretch near the lake and can be fished with a variety of techniques. There are probably also more obvious access points.

- Alum Creek to Chittenden Bridge runs from the end of the 8-mile Hayden Valley closure zone down to Chittenden Bridge. This stretch is broad and has few distinguishing features, but it’s often swift due to the falls not far downstream. It is generally right next to the Canyon–Lake Road, but it seldom gets fished. Why? Fish populations were never as high here as they were close to the lake. Nowadays, there are very few. If you see risers, by all means stop. Otherwise, head closer to the lake.

Access to all sections just noted is easy. Much of it is in sight of the road and there are numerous pullouts. The map below holds a few landmarks and less-obvious access points. Despite easy access, this water is seldom crowded. This is because of the difficulty of the fishing. This is definitely not a place to take beginners.

Lower Falls to Lamar River Confluence – The Grand Canyon

The Yellowstone River changes character utterly near Chittenden Bridge. Whereas upstream it’s a large but often gentle river home to vast numbers of insects and a vast variety of them, and small numbers of large fish, downstream of this point it’s a raging whitewater canyon river all the way to Gardiner.

It’s still home to lots of bugs, but more of them are large stoneflies compared to points upstream, and there are fewer important species overall. Fish populations still center on cutthroats, but instead of a small numbers of big fish, there are lots of midsize fish in great condition. There are also some rainbow and brook trout. Access changes too: there’s very little of it. Except for one bridge crossing and a couple relatively easy official and unofficial trails, all access to this water requires brutal hikes of several miles plus dramatic elevation change.

While the transition from the water near the lake to the Grand Canyon is obvious (two of the world’s most famous waterfalls mark the beginning of the canyon proper), there’s some argument about where the Grand Canyon ends and the Black Canyon begins. Many authors place the change near the Tower Falls area (Tower Falls is on Tower Creek, the largest tributary in the Grand Canyon). I place the transition at the mouth of the Lamar River, since the Lamar dramatically enlarges the Yellowstone, can muddy it for days at a time, and shifts the temperature regime (warmer in high summer, colder late in the year).

Grand Canyon structure in September. In early July, those midriver rocks are underwater.

The canyon between the falls and the Lamar deserves the title “Grand.” It is one of the country’s deepest canyons, over 1500 feet deep in places and almost always several hundred. Often these canyon walls rise almost vertically from the river. While the Yellowstone near the lake can be more than 100 yards across, I can actually cast completely across the river in a few places in the Grand Canyon. Not that such places are productive. The water was probably 60 feet deep where I’ve done it.

As befits its canyon nature, this stretch of the Yellowstone is fast, deep, and turbulent. While there are no official waterfalls on this stretch except those at the upstream end, there are innumerable heavy rapids. Wading is therefore treacherous. Most areas, it’s unwise to wade over your knees. There are several island complexes upstream from the Tower Creek confluence, but for the most part the river flows as a single torrent in the Grand Canyon. This all adds up to mean that crossing the river is impossible most places. The main exception is in the largest island complex upstream from Tower Falls, where’s it’s possible for a strong wader to cross the river in September and October during low-water years. Otherwise, you’re stuck on the side you’re on.

While it occasionally fishes well from the beginning of the park season as noted above, the Grand Canyon comes into its own in late June and July. The fishing at this time centers on Salmonfly, Golden Stonefly, and scattered other hatches. I usually have a spare rod rigged with streamers while my clients fish nymphs or dry-dropper, depending on the progress of the hatches. By mid-July, it’s usually possible to fish dry-dropper with a large dry and midsize nymph (a Chubby Chernobyl with a large beadhead Prince, for example) all day without changing. The secret is to keep moving. Easier-access areas actually get fished pretty hard, but the fish tend to pod up even in areas that don’t get pounded. One good-looking run will not have any feeding fish, while the next can hold literally dozens of trout. Most run 8–16 inches, but there are occasional trout to 20 inches.

In August, switch out the attractor dry for a grasshopper and move to a mayfly-style dropper nymph. By late August, fall hatches of BWO and Tan Drakes can begin, of which the BWO are by far the most important. These hatches intensify in September and are best on cold, cloudy days. September flurries or even full-blown snowstorms often bring heavy afternoon hatches. Absent a hatch, streamers are usually better than nymphs in the fall, though sometimes it makes sense to fish a streamer under a strike indicator in the deepest, narrowest slots.

The fishing tails off through October but doesn’t quite die by the close of the season. Small hot springs and especially the moderating influence of immense Yellowstone Lake upstream explains why this water holds on while much of the other water in YNP gets very tough in October. Afternoons are certainly best in October.

Access to this stretch is very limited and very difficult. The Grand Canyon can be divided into three stretches as far as access, though all fish about the same:

- The Upper Grand Canyon begins from a fishing perspective opposite Silver Cord Cascade, on tributary Surface Creek. This is a 1200-foot waterfall, the park’s tallest though far from the largest. In effect, this section of canyon is accessible only via the area known as Seven Mile Hole. This is a brutal 5.5-mile hike from the Glacial Boulder Trailhead near Canyon Village. There’s 1500 feet of vertical descent in the last mile and a half down to the water. Most anglers camp at one of the many backcountry sites rather than trying to tackle the climb out on the same day they hiked in. Carry many water bottles and plan four hours for the hike out.

- The Middle Grand Canyon runs from the bottom of Seven Mile Hole several miles to the confluence with Agate Creek. Except for the Agate Creek Trail, this section of canyon is completely inaccessible. Agate Creek is an even harder hike than Seven Mile Hole. It begins at the Specimen Trailhead on the East Entrance Road near the Yellowstone–Lamar confluence and involves a serious climb prior to a comparable descent to the river as Seven Mile Hole. At 7+ miles one-way, this is strictly an overnight destination.

- The Lower Grand Canyon is much more accessible and Livingston or Gardiner are very reasonable places to stay to fish here. The Northeast Entrance Road bridge and an adjacent but unsigned parking area on the northern side of the east side of the bridge offer so-so fishing. Right under the bridge sees heavy pressure, but it’s possible to scramble upstream on the east side of the bridge perhaps a mile. This is actually a better access for the upper Black Canyon a couple miles downstream. Better access for the Lower Grand Canyon is found via the beginning of the Specimen Ridge Trail (see the map for specific details on this access, as it gets weird), via the Tower Falls parking area and trail, and via a very rugged albeit short set of game trails near Calcite Springs (see map for details). The Tower Falls Trail provides by far the easiest access at about 300 vertical feet down to the river on a half-mile switchbacked trail, with about 2mi of river accessible once you’re near the river (though over half a mile of steep bank is covered in downed trees and best avoided). Probably 90% of the Grand Canyon’s overall fishing pressure occurs either at the bridge or at the Tower Falls access.

Lamar River Confluence to Gardner River Confluence – The Black Canyon

The Black Canyon of the Yellowstone runs from the mouth of the Lamar about twenty miles to the mouth of the Gardner River, the park boundary. While portions of this canyon have sheer black rock walls (which give the canyon its name, probably), they are never as high as those in the Grand Canyon. Rather than death-marches involving over 1000 feet of vertical in many cases, the hikes into the Black Canyon require anywhere from no more than a hundred feet of climbing on up to 800 feet spaced over four miles. You can make a three-day hike through the Black Canyon if you like—and encounter great fishing all the way–but there’s no need to. Many sections of the Black Canyon are only a couple miles from the road, which puts them well within day-trip range for anglers of solid but not spectacular fitness. One note: the banks are almost always rough and rugged, choked in large boulders and the like.

Overall the Black Canyon provides less consistent fishing than the Grand Canyon, both in terms of when it’s fishable and in terms of the day-to-day willingness of the trout. The trout do seem to run larger than in the Grand Canyon, however, especially upstream from Knowles Falls six miles upstream from Gardiner. The archetypal fish here is a 15-inch cutthroat that’s very fat for its length. Rainbows gradually grow more common, as do whitefish, and browns join below Knowles Falls.

The when about fishing the Black Canyon is entirely due to the Lamar River. This is the Yellowstone’s largest tributary between its headwaters and the Stillwater River 150 miles downstream, and it often runs muddy, both during the prolonged spring snowmelt and a couple days after summer thunderstorms. When the Lamar is muddy, it’s pure filth that looks like you could walk across it. It makes the Yellowstone just as muddy. Beyond the mud, the Lamar also yo-yos in temperature. In late summer it’s much warmer than the Yellowstone upstream, while in the fall it’s colder. Again, this makes the Yellowstone downstream yo-yo as well.

Tactics are similar in the Black Canyon as in the Grand Canyon, save for the fact this water is almost never fishable prior to about June 20. July 4 is more likely. The best fishing is in late July and August. The Salmonfly and Golden Stonefly hatches kick off the season, while hoppers are the stars in August and early September. BWO and Tan Drake hatches occur in the fall, though the Tan Drake hatches are not as consistent as they are in the Grand Canyon. Streamer fishing is also a good bet here, especially upstream from Knowles Falls.

In terms of character, the Yellowstone remains fast, deep and brawling in most of the Black Canyon, and Knowles Falls is a small but real waterfall on the mainstem of the river 6mi upstream from Gardiner. Several gorge areas are every bit as rough as the roughest portions of the Grand Canyon. That said, the river does spread out into a heavy riffle-pool stream in a few places, and it’s possible in the fall to wade out to many islands in the middle of the river, a rarity upstream.

One important note about the Black Canyon is that a small portion of it is outside the Park. This stretch is located 2mi upstream from Gardiner and is centered on the mouth of Bear Creek (which is entirely outside the park). In practice, if you’re fishing the north bank of the river near Bear Creek, be sure to have a Montana license as well as or instead of a Yellowstone Park license.

There is no road access to any portion of the Black Canyon. There are many trails, however. The Yellowstone River Trail parallels almost the entire canyon on the north side of the river, while the Garnet Hill Loop Trail parallels the upstream end of the canyon on the south side. Here are the official and unofficial trailheads that make sense to access the canyon:

- The Northeast Entrance Road Bridge and Lamar Confluence Trail provide access to the upper end of the canyon. Either hike downstream from the bridge past the mouth of the Lamar (which comes in on the opposite side of the Yellowstone) or down the Lamar Confluence Trail and cross the Lamar. Though unofficial, both areas have good and obvious game/angler trails. Note that the bridge access is not for those with a fear of heights. Near the beginning the trail climbs along the flank of a vertical dirt cliff directly above the river.

- Hellroaring Trailhead: A short but steep hike down to the immediate rim of the gorge over the river connects to the Garnet Hill Loop Trail as well as an angler trail down to the mouth of Elk Creek. Otherwise, continue on the Hellroaring Trail as it crosses the river via a bridge and transforms into the Yellowstone River Trail. It’s possible to hike all the way back to Gardiner via this trail, and there are numerous backcountry campsites both along the river and any tributaries. Note that the trail is often a mile or so north of the river.

- Geode Creek Bushwhack: This is probably the hardest access that makes much sense for a single-day trip. Take faint game and angler trails down the west side of Geode Creek 2.5mi to the Yellowstone. The parking area is a tiny splat of gravel adjacent to the almost-invisible creek. Stick to the hillside on the walk down to the Yellowstone. The meadows are full of mosquitoes and marsh.

- Blacktail Deer Creek Trail: This 4mi trail descends 800 feet to the river, but it’s gradual. The trail connects to the Yellowstone River Trail via a bridge over the river, and there are many connector trails and backcountry campsites near the mouth of Blacktail Deer Creek. Plenty of hikers through-hike in a day from here to Gardiner (or vice-versa), but it’s a full-day hike even without any fishing.

- Yellowstone River Trail – West End: The Yellowstone River Trail now heads from Eagle Creek Campground a couple miles up (very up) the Jardine Road from Gardiner. It formerly began right in Gardiner at the LDS temple. Unfortunately, the landowner whose property the trail crossed on an easement didn’t like teenagers partying on his beach and closed the easement. Instead of less than 100 feet of vertical descent on a partially-shaded trail, the climb down to the river is now steep, brutally hot, and perhaps a thousand feet of vertical. The trail reconnects with the old trail near the mouth of Bear Creek. Note that much of this area is outside the park boundaries and requires Montana licenses.

- Rescue Creek Trailhead: Cross the Gardner River via the adjacent footbridge and either walk down the angler/game trails parallel to the Gardner to the Yellowstone or take the Rescue Creek Trail until its closest approach to the river, then cut over. The former is less than a mile. The latter is a bit over. Note that the status of this access is up in the air following the 2022 flood. The footbridge was destroyed and the road rerouted away from the Gardner, so it’s possible this trailhead will not be rebuilt.

- Gardner River Mouth: Take the obvious gravel path (really a jeep road) from the cul-de-sac on Park Street in Gardiner down to the mouth of the Gardner River. Wade across the gravel bars right at the mouth of the Gardner and fish upstream on the Yellowstone. Via game/angler tracks on top the sporadic cliff bands, this access connects to the same water accessible via Rescue Creek Trailhead, but this walk is shorter. The Gardner River may be forded by strong waders after mid-July most years, sometimes August 1. Note that the Yellowstone downstream of the Gardner is in Montana, while the entire Gardner and Yellowstone upstream are in YNP. Have both permits if you want to fish down into Gardiner as well as up into the park.