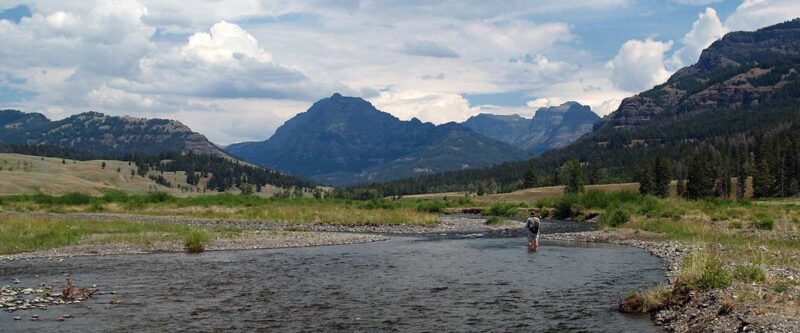

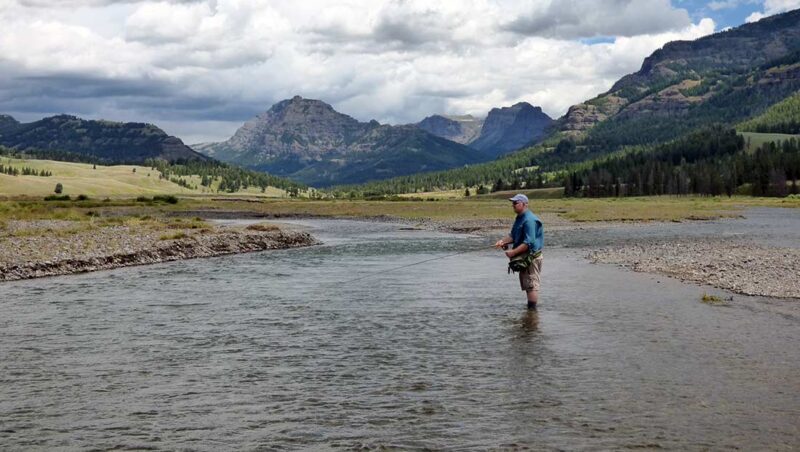

Yellowstone Park's most-beloved, but also most crowded meadow streams, the Lamar River and its tributaries Soda Butte and Slough Creeks

In their most popular stretches, the Lamar River and its main tributaries Soda Butte and Slough Creeks are gentle meadow streams with glorious scenery, lots of wildlife, and lots of solid cutthroat trout. Both the Lamar and Soda Butte are also extremely easy to access in their most popular stretches, never more than a mile from the Northeast Entrance Road and often feet from it, while Slough offers a mix of roadside fishing and hike-in fishing along one of the park’s most popular trails.

Easy access, good fish and fishing, and beautiful scenery combine to mean one thing: intense crowds of anglers. While it’s possible to get away from people by fishing rough sections of the Lamar and Slough Creek or by hiking up the Lamar, all other areas of these three streams see overwhelming angling pressure. On all of lower Soda Butte Creek and roadside sections of the Lamar and Slough Creek, it’s often impossible to get 100 yards to yourself. The easiest-access portions of Soda Butte feet from the road can become almost shoulder-to-shoulder. Even hiking 5+ miles into Slough Creek’s Second Meadow won’t shed everybody, since this is an extremely popular hiking, horseback destination, and backcountry camping area.

The scenic charm of the Lamar River system is undeniable, but seeing it without a bunch of people is rare.

So what’s the verdict? That’s up to you. For Yellowstone Country Fly Fishing, the tradeoff is seldom worth it. We’ll fish the rough areas and less-busy hike in stretches, or maybe pay a visit to the gentle stretches late in the season after the crowds (but also the fishing quality) begin to fade, but we try not to fish or guide this water during the core season. Beat-up trout that get caught dozens of times per season, trout that are festooned with hooking scars, broken jaws, and sometimes missing eyes and fins just aren’t what we’re looking for, even if they are big and the hatches are good.

To avoid the crowds, the tributaries of the Lamar and Soda Butte Creek offer good hike-in fishing, though the trout aren’t as large. Learn about these tributaries on the Small Streams Page.

Note that most areas in the Lamar System are not suitable for beginner fly fishers. The easiest areas are the fast water sections of Slough Creek and the Lamar, while the hardest areas (experts only) are the lower end of the Lower Meadow of Slough Creek. Otherwise, this water is suitable for intermediate and better anglers, or patient beginners with guides who would rather catch a couple fish than a bunch of little ones.

- Learn about our Walk & Wade Guided Trips. We mostly guide rough portions of Slough Creek and the Lamar except with older, creakier anglers. With them we bite the bullet and visit Soda Butte.

- Soda Butte Creek Stream Gauge: Sudden spikes in this gauge mean Soda Butte Creek is muddy and the most popular stretch of the Lamar soon will be. The best flows for fishing are under 150cfs.

- Lamar River Stream Gauge: Sudden spikes in this gauge mean the Lamar Valley and Lamar Canyon are muddy, but it’s possible the upper Lamar, Soda Butte, and Slough Creek are clear (but probably crowded). The best flows for fishing are under 1,000cfs (500 even better).

Lamar River System – Description

The Lamar System drains the northeast part of Yellowstone Park. The Lamar flows entirely within the park’s boundaries, while Soda Butte Creek and Slough Creek start just outside the boundaries. Both are small creeks outside the boundaries, but mature trout streams inside the park.

While all three streams (and other small tributaries, which are discussed on the small stream page) have some canyon sections, and Soda Butte in particular flows in a wooded valley for more than half its length in Yellowstone Park (though not where it’s most popular), all three are most known as riffle-pool meadow streams flowing through open valleys covered in grass and sage, and only sparsely interrupted by small groves of aspen or pine trees.

All three streams see intense mayfly hatches over much of the season, and the mayfly and terrestrial fishing in late summer are the primary drivers of the Lamar System’s fame. The fishing season is short, however. All three streams have a quality season less than three months long in normal years. The high mountains in the headwaters make for an intense spring snowmelt that seldom begins to recede before the beginning of July, and often ten days later. There are few hot springs in the Lamar System compared to other rivers in the park, and the shallow, riffle-pool nature of the system allows for rapid cooling when the weather turns, so things shut down early in the fall, too. Even September mornings can be very slow, while in October winter-style tactics and flies (nymph-fishing with midges in the warmest part of the day, for example) may be required.

“Bread and butter” cutthroat in the Lamar Drainage are about this size.

Besides the short season overall, fishing is often interrupted by summer showers. A little rain in the valleys doesn’t hurt anything, and can make for better hatches, but rain in the headwaters of the Lamar and Soda Butte leads to muddy water. The headwaters of both streams are steep, bare, and highly erosive. The local joke is that the Lamar (and Soda Butte) get muddy when an elk pees in the wrong spot. Slough Creek seldom gets dirty after runoff recedes, but the crowds can be so intense when it’s clear and its sister streams aren’t that it really isn’t worth your time.

The Lamar Valley has been called “America’s Serengeti.” It’s a more accurate description than you might think. Very large numbers of bison, elk, and pronghorn live here, and in the winter there are often bighorn sheep. Non-native mountain goats live on the steep mountainsides along upper Soda Butte Creek, and moose also lurk in the woods. The park’s largest concentrations of wolves and grizzly bears inhabit the area, and there are also lots of black bears and smaller predators such as coyotes, badgers, and foxes. The wildlife watching here is at least as good as the fishing. If you want to see a bear or wolf, look for the crowds with spotting scopes and camera lenses that look like they should be installed in an observatory somewhere.

Lamar River System – Waters

While the Lamar River has several good tributary creeks in it headwaters, Soda Butte Creek has one fishable tributary creek, and there are a couple great lakes in its system, the real stars of the show in the Lamar System are the three main streams, which are also the largest streams in the basin.

Lamar River

The Lamar River begins near the park’s eastern boundary near the crest of the Absaroka Range. It feeds the Yellowstone River more than 30 miles downstream of the Lamar’s headwaters at the head of the Yellowstone’s Black Canyon.

A small westward-flowing stream in its trailless headwaters, it becomes a worthwhile fishery near the confluence with Cold Creek. From here it flows northwest and is followed by the Lamar River Trail. The Lamar is still a small gravel-bottomed riffle-pool stream here, but it holds lots of 12″ trout and is a popular overnight destination, especially for anglers who would rather catch small trout without crowds than big ones with crowds.

The Lamar comes within day-hike range of the road near the Cache Creek confluence, about a 4-mile hike from the road. Pressure steadily intensifies between the Cache confluence and the Soda Butte Creek confluence, where the Lamar hits the road. Between the creeks, the Lamar first flows in a vertical-walled gorge. Despite this, the river is generally slow-moving and shallow, and offers poor habitat. At the crossing for the east end of the Specimen Ridge Trail, the river enters the upper reaches of the Lamar Valley. From here to Soda Butte, the Lamar flows through a broad and shallow channel, meandering from one channel to another with every spring runoff. Most of the habitat is poor, basically shallow riffles and broad ankle-deep pools, but the few deeper areas hold lots of fish averaging 10–16 inches. You’ll have a to walk a while to find them, though.

From Soda Butte downstream, the Lamar is never more than a mile from the Northeast Entrance Road and often a matter of feet.

The heaviest pressure occurs in the 8 miles between Soda Butte and the beginning of the Lamar River Canyon. This stretch, the core of the Lamar Valley, is a wide meadow through which the river meanders. In most stretches, one long pool is separated from the next by a riffle. In a few places, the river splits into channels around islands. Buffalo herds often prevent anglers from walking across to the stream. If they aren’t in the way, this is good water. It sees excellent Green Drake and PMD hatches in the summer, but it is most-known for its terrestrial fishing. While exceptionally large hoppers once ruled the day, nowadays ants and beetles are more effective. You should still carry some of the big stuff, though. The average fish run 12–18 inches.

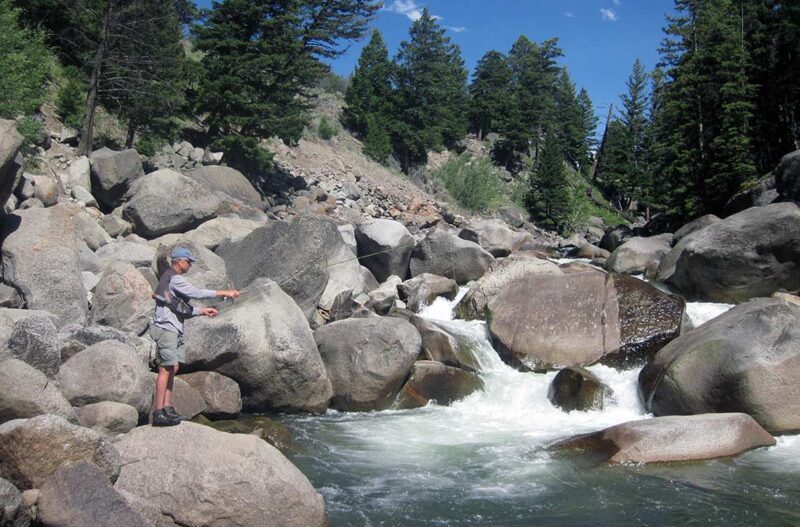

The upper Lamar Canyon is extremely rugged, even if it is right next to the road.

The Lamar Canyon has two distinct sections. The upper section, from the bottom of the Lamar Valley to the Northeast Entrance Road Bridge, is feet from the road but in a vertical-walled gorge. The river is deep, narrow, and in many places extremely fast and steep. The bottom and canyon walls are composed of solid rock and boulders the size of cars, including the largest stretched SUVs. Areas of this portion of the canyon that aren’t quite so treacherous to access see moderate pressure, while the treacherous spots are in some cases completely impassable and in many others very dangerous and suitable only for the most surefooted and fit anglers. Large attractor dry-dropper combos can work here, as can streamers. There’s also an inconsistent Salmonfly hatch in early July just as the river clears, as well as Green Drakes and hoppers. The fish average 8–16 inches, but very large ones are possible. I have never seen one much over 20 inches, but I’ve seen pictures of fish exceeding 24 inches.

The lower section of the Lamar Canyon has a few steep, narrow, and nasty spots, particularly near the confluence with Slough Creek and near the Yellowstone confluence, but the river is more commonly wide and surprisingly slow-moving, down in a bit of a divot in the surrounding prairie and with a bed full of somewhat smaller boulders than the upper canyon. Areas within sight of the road see heavy pressure, while the steeper and nastier sections don’t see much pressure at all. That said, the fish are scattered in the lower canyon, since a lot of the water is poor habitat. When you find good areas (which will take some walking), the fish run 8–16 inches with a few bigger ones.

Soda Butte Creek

Several small creeks come together to form Soda Butte near Cooke City, Montana, about four miles northeast of the park boundary. Soda Butte then flows southwest about 20 miles to its confluence with the Lamar. This entire distance, it’s never more than a mile from the Northeast Entrance Road (Hwy 212 outside park boundaries) and often much less. Throughout its length, Soda Butte averages about 20–30 feet wide, though it’s much deeper in its lower reaches. Soda Butte has three personalities, of which two are of interest to anglers.

Soda Butte’s first personality is found from Cooke City downstream to the exceptionally narrow vertical-walled gorge called Ice Box Canyon, a distance of about 11 miles in total. In this stretch, Soda Butte is a wooded mountain creek flowing in fast riffles and brief pools in a steep valley choked in timber, interspersed with a few small meadows. It is usually out of sight of the road down steep game trails through the trees. Despite being out of sight, this stretch still isn’t “out of mind” and it’s not uncommon to find most pullouts occupied by anglers. That said, the pullouts are far apart, so it’s easier to shed people here than elsewhere on the creek. This stretch of Soda Butte fishes best in August and early September and holds fish that average 8–14 inches, though they can get big once in a while.

Soda Butte’s second personality is raging, difficult-to-access canyon that isn’t really worth fishing. This water is best exemplified by Ice Box Canyon. This narrow, vertical-walled gorge is so shady that winter’s ice often clings to the canyon walls into July. The canyon is about 3mi long, is impossible to access except (with difficulty) by walking downstream from the stretch above or upstream from Round Prairie below. This stretch holds few trout larger than your hand except during the early July spawn. The same is true of the shorter 1-mile canyon called the Trout Lake Rapids a couple miles downstream. Trout Lake Rapids sees much heavier pressure since it’s right next to the road, but this pressure isn’t warranted unless you like fishing for tiny trout that get fished to much harder than they should.

Soda Butte’s third personality is found in one-mile Round Prairie downstream of Ice Box and four-mile Junction or Lower Meadow downstream of Trout Lake Rapids. In these meadows, Soda Butte is a gentle riffle-pool meadow stream, with innumerable bends, undercut banks dropping into deep holes, and numerous side channels which often remain deep enough to fish well through August. The meadows see the vast majority of Soda Butte’s angling pressure, which is no surprise since I have guided anglers on crutches in the meadows (though that was a stretch), the trout are hefty (they average 12–18 inches), and the hatches are strong. The hatches are really the stars of the show here. They’re more consistent than elsewhere in the Lamar System, with at least some mayflies hatching almost daily from early July through late September.

The issue with Soda Butte’s meadows are the crowds. It is more likely than not that every single pool in both meadows will be occupied most of the day from early July through late September here. It’s often so crowded that the pullouts along the Northeast Entrance Road are completely full. This is the most crowded water in Yellowstone Park for the entire summer; it is virtually impossible to fish out of sight of other anglers except in the evening. This is one stream I’d fish all the time if it were 3mi off the road. Since it’s right next to the road, I never fish it for fun (I haven’t done so since 2007), and I only guide any portion of Soda Butte when I have anglers with poor fitness or who insist on fishing the stream. This only happens once or twice a season. The angler photos in Soda Butte’s Meadows on this website were almost all taken prior to 2010 for this reason.

Slough Creek

Slough Creek begins north of Yellowstone Park in the Absaroka-Beartooth Wilderness and flows southwest perhaps 15 miles to join the Lamar a couple miles upstream from the Lamar’s confluence with the Yellowstone. Slough becomes a mature trout stream a couple miles north of the park boundary in a meadow called Frenchy’s Meadow, the first of five named meadows on the creek. While it’s more than a dozen miles off the road, even this stretch of Slough sees some fishing pressure. There’s a high-end guest lodge just north of the park boundary accessible only via horseback or wagon. The lodge sends its anglers all over within a couple miles of the lodge. You can’t go, don’t ask. This is the sort of place that doesn’t have a website and where the staff outnumber the guests. I have no idea if it’s accurate, but the number I heard once was $50,000 per week. I do know the guests think nothing of dropping $1000 on flies before their horseback ride in.

Once it enters Yellowstone Park just south of the lodge, Slough Creek is followed at a distance of a few yards to half a mile by the Slough Creek Trail. The trailhead is about ten miles southwest of the park boundary. Heading upstream, it first crests a nasty hill, then follows a much more gentle grade past Slough’s First, Second, and Third Meadows, as measured from the trailhead. The First Meadow is 2mi off the road, the Second a bit more than five miles, and the Third eight miles. Only a short screen of trees separates the Third and Second Meadows. A half-mile canyon separates the Second Meadow from the First and a much nastier and somewhat longer canyon (the Slough Creek Canyon) complete with a couple small waterfalls separates the First Meadow from the trailhead area, the Slough Creek Campground area, and the creek’s final meadow, the Lower Meadow. Beyond the Lower Meadow there’s a half-mile canyon through which Slough dumps into the Lamar.

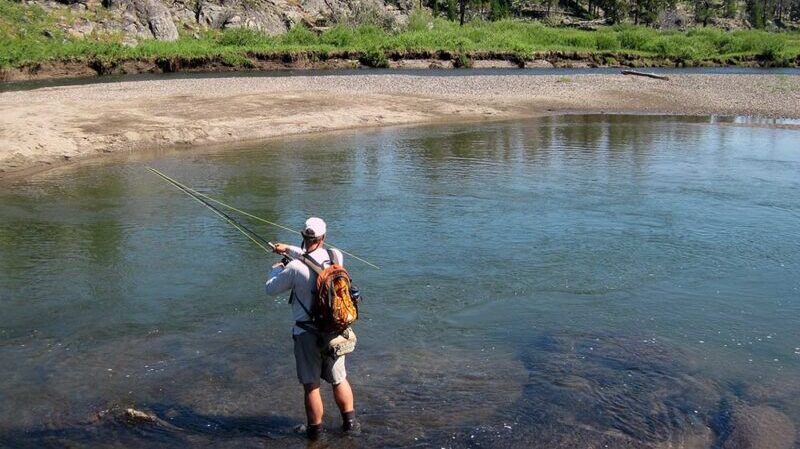

The three “Upper Meadows” are the most-fabled water on Slough Creek and collectively rank in the top three favorite areas to fish in the park. Here Slough runs 30 or forty feet wide, with short riffles feeding into longer pools. The stream meanders this way and that through the meadows. The fish average 14–18 inches, with many fish in the 20-inch class. Good hatches are possible in July, but terrestrial fishing is even better. Numerous backcountry campsites in the Second and Third Meadows provide overnight access for both backpackers and horse outfitters. Every campsite will be full from July through mid-September. The only way to get one is via a spring drawing. While there are some stands of trees here and there, the Upper Meadows are mostly situated in open grass and sage.

The gorge sections are wooded and choked in boulders. Some areas are steep and flow as pocket water, but there are numerous pools even in the canyon stretches. Access is very difficult, as the banks are treacherous and often choked in downed trees after a serious of fires several years ago. There’s an unofficial trail into the bottom 2/3 of the gorge between the First Meadow and the Campground area and a fainter one near the confluence with the Lamar, but only game tracks elsewhere. The fish in the gorges range from fingerlings up to about ten inches on average, but the gorges are used for spawning and insect activity is intense enough even in the rough water that some of the big fish stay until sometime in August. If your party is surefooted, the gorges are thus good places for total beginners to learn the ropes on little fish while hoping for a shot at one big one as well.

The campground water is something of a transition between the Slough Creek Canyon and the Lower Meadow. While it’s wooded, the upper end of this water (running from about 500 yards above the campground to a couple hundred yards below) is a series of slow and often silt-bottomed pools. If there’s a hatch, it can be good. No hatch, you’d swear there are no fish. The lower portion, which runs right through and just beyond the campground, is modest-gradient pocket water that fishes similarly to the gorges.

The Lower Meadow of Slough Creek is either right beside the Slough Creek Campground Road or no more than a mile-long, flat and easy hike from it. While there’s a series of riffle-pool combinations at the upstream end that offer comparable fishing to the Lamar Valley or Slough’s Upper Meadows, this water is generally dead-flat and slow-moving. It’s probably where the stream got its name, because it resembles a lake more than a stream in many places. The fish here are big: 14–20 inches on average, though there are some fingerlings mixed in. There are some trout in the 24-inch class, one of the few places in the Lamar System for which this number isn’t a wild exaggeration. Even the small fish can be extremely difficult. The big ones demand long, fine leaders, tiny flies, and careful approaches and casting. Despite this difficulty (this is probably the second-hardest fishery in Yellowstone Park, after the remote Bechler River Meadows in the park’s southwest corner), the Lower Meadow sees intense pressure since it is very easy to access.

Lamar River System – Directions & Access

Access to the Lamar River System is no trick. The Lamar is paralleled by the Northeast Entrance Road throughout the Lamar Valley and Lamar Canyon stretches before peeling off into the wilderness. Access upstream is via the Lamar River Trail, which has two trailheads (one for stock, one for hikers) about a mile up Soda Butte Creek. Soda Butte is followed by the Northeast Entrance Road aka Hwy 212 throughout its entire length. Slough Creek is accessible via the gravel Slough Creek Campground Road and the Slough Creek Trail.

Not including hike-in areas, all of this water is within about 90 minutes of Gardiner, making Gardiner by far the best Yellowstone border community for accessing this water while still remaining within easy reach of other fisheries. Cooke City and Silver Gate at the park’s NE Entrance are even better for the Lamar System, but too far from almost everything else. Since the Lamar System often becomes unfishable due to summer storms, you’re rolling the dice if you decide to stay in Cooke City/Silver Gate or at Slough Creek or Pebble Creek Campgrounds located in the Lamar System.

Angling

Fish Populations

There are no brown trout in the Lamar System. If you catch a trout that’s bronze-brown-gold in color, it’s a male cutthroat with impressive coloration and must be released. LOTS of pretty mature male cutthroats get killed by stupid anglers in the Lamar System who are convinced anything dark-colored must be an “invasive brown trout.” The Park Service has a good rule of thumb: “if it has a slash, put it back.” Any red, pink, or orange on the jaw, release the fish.

- Yellowstone Cutthroat: Yellowstone cutthroat trout are the only native fish in the Lamar System and dominate the fish populations. Their size is highly variable depending on the structure. With a few exceptions, meadow areas hold larger fish and canyon areas serve as spawning and nursery areas. In early summer the canyons hold a few big fish that haven’t returned to the meadows after spawning yet, plus vast swarms of small trout seldom larger than nine inches. Trout in the meadows average 12–18 inches and routinely reach 20 inches, though seldom get much bigger than that. The only canyon that often holds larger trout all season is the Lamar River Canyon. The fish average 8–16 inches there.

- Rainbow and Rainbow-Cutthroat Hybrid (Cuttbow) Trout: Populations of rainbow and hybrid trout rapidly increased beginning during the early 2000s drought, particularly in the Lamar proper downstream of Soda Butte Creek and in lower Slough Creek. All rainbows and recognizable hybrids must now be killed. The rainbows tend to run small, under 12 inches. Some very large hybrids are possible. I have seen several in the 24-inch class in Slough Creek and know of others caught in the Lamar. I’ve never seen a fish over 22 inches in Soda Butte of any species.

- Brook Trout: It is exceptionally unlikely you’ll see anything but cutthroats and rainbows/cuttbows, but if you encounter a brook trout, kill it, keep it, and show it to Park Service officials. Brook trout were once stocked in upper Soda Butte Creek. An aggressive repression effort several years ago SHOULD HAVE cleared them all out. If any stragglers are still present, the Park Service needs to know about it.

Lamar River System Fishing Season – When It’s Open & When It’s Good

The entire Lamar System opens with the park’s general season on the Saturday of Memorial Day Weekend. That said, none of the three streams in the system is typically fishable at this time. Occasionally Slough Creek is clear enough to fish with streamers for a few days after the opener before it blows out with the worst of the spring melt, but this is unusual.

More commonly, the Lamar, Soda Butte, and Slough all come into shape sometime in early July. Slough Creek comes into play first, usually between July 1 and July 10. Rough portions of the Lamar (Lamar Canyon) and lower Soda Butte Creek come in a few days later. Gentle sections of the Lamar come in a few days after that. Upper Soda Butte runs clear the same time as lower Soda Butte, but it’s ice water. It becomes fishable in an average year around July 15, but it’s much better in August. Shift all of the above dates a week to ten days earlier in drought years. I have never seen any of the major waters in the Lamar System come into play post-runoff prior to June 20.

The fishing is best for the month following the dates above, then gets harder and less consistent overall through the remainder of the season except during hatches. The hardest fishing of all is on hot, bright late August and September afternoons, followed by cold mornings in late September. October fishing is very limited due to cold water. Ice is possible in backwaters by this time, and it’s very common for the main flow not to get out of the low 40s even in midafternoon.

Lamar River System Fishing Tactics

Dry fly fishing is the name of the game in the main streams of the Lamar System. Hatches almost always offer the best fishing. Assorted species of Green Drakes are the main insects. These begin with #10–12 bugs (probably Drunella doddsi for the Latin speakers) in July, which gradually shade down to similar-appearing bugs in #14–16 (perhaps D. flavilinea or D. coloradensis). A few of the full-size bugs hatch all summer at higher elevations and again at lower elevations in September. It’s important to note that these Green Drakes are predominately gray in color. They have all the habits of Green Drakes, but Gray Drake patterns are often more effective. A few brighter Green Drakes (probably D. grandis) pop in September.

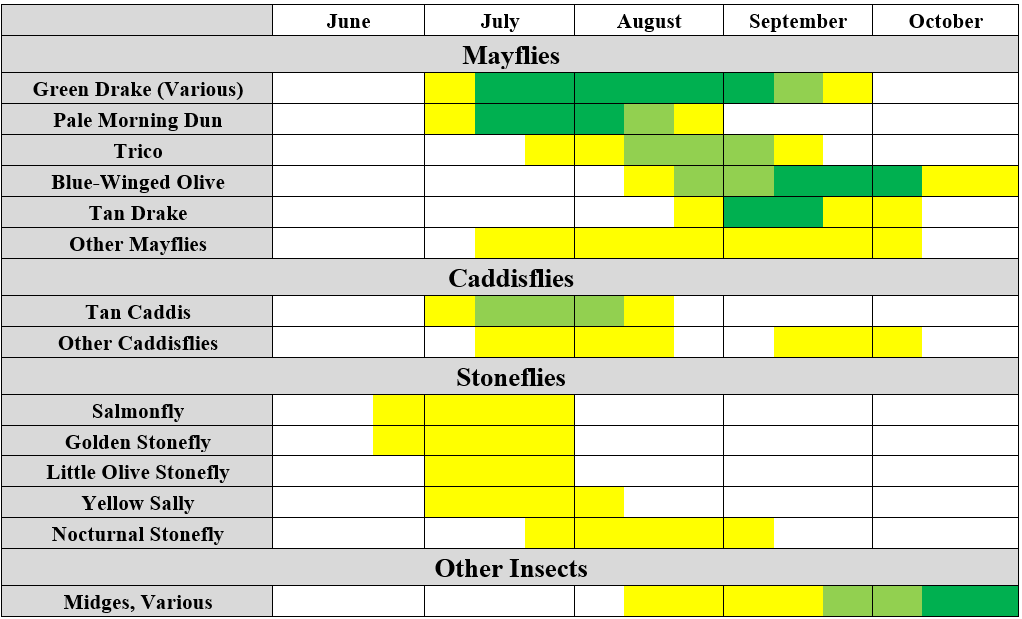

Other important hatches that will make the trout selective include Pale Morning Duns in July and August and fall gray Blue-winged Olives (again, gray with just hints of green) in late August and September. Tan Drakes, aka Drake Mackerals (probably Timpanoga hecuba) hatch in late August and September. A smattering of other mayflies are also present, there are Tan Caddis in late July and early August, and Yellow Sally and Little Olive Stoneflies can occasionally get the fish excited in late July. Midges are about the only common insects by October, and they can also hatch on September mornings.

Several species of “Green Drake” mayflies from #10 to #16 are the most important food sources in the Lamar System. This was a #12 photographed in August on upper Soda Butte Creek.

In July and August, hatches usually occur from midmorning to early afternoon, with some late evening hatches or spinner falls also possible. In September, hatches are much more common in midafternoon. Fishable hatches in October are sporadic and may not happen at all.

Absent a hatch, fishing hopper-dropper combos (the dropper can often be an ant or beetle instead of a nymph) is the best tactic from late July through early September, while in early July right after runoff, large streamers can often work best. Nymphing with strike indicators is not a common tactic here. About the only spots deep-nymphing is called-for are in Soda Butte Creek and rocky areas of the Lamar. It is almost never effective on gentle sections of Slough Creek, where the splash of a strike indicator or even a heavyweight nymph will almost always spook every fish in sight. Go small on your nymphs. Thread-bodied midges and mayfly nymphs no larger than #16 are usually best.

Fishing the structure makes the most sense on Soda Butte Creek, where the riffle-pool combinations are closer together than elsewhere. It also works on the Lamar, though you’ll want to walk past the bottom 2/3 of each pool most of the season. On Slough Creek, fishing “blind” is seldom effective in the meadows, especially the Lower Meadow which in many areas seems as slow-moving as a swimming pool.

On all three streams, the greatest success comes via sight-fishing. If hatches are underway, target specific rising trout. If no hatch is underway, target specific trout underwater with terrestrial dries or nymphs. Ants fished “drowned” are often highly effective when there’s no hatch. Try to find trout that are sitting up in the water column and obviously feeding—moving side to side, opening their mouths to take nymphs, etc. Trout that are just sitting motionless on the bottom are unlikely to feed, especially on lower Slough Creek.

The main exception to all of the above are rough water sections of the Lamar and Slough Creek. The rough sections of Soda Butte Creek are not particularly interesting to most anglers, since they see heavy pressure despite holding few fish larger than your hand. In these areas, typical rough-water tactics can apply in addition to all of the above. In other words it makes sense to fish large hopper-dropper combos with something like a beadhead Prince on the dropper, streamers, stonefly nymphs, and big attractor dry flies, targeting the structure. When a hatch begins, switch to high-floating imitations of the insects you see. Green Drakes are the most important hatch in these rough water areas, but Salmonflies and Golden Stoneflies are also possible in July. These big stoneflies are basically absent on gentler sections of stream in the Lamar System.

Rough water stretches in the Lamar System hold mostly smaller trout, but there are exceptions.

Insect Hatches & Other Prey

The following table provides info on important insect hatches for the Lamar System. The best hatches occur on Soda Butte Creek, the least-consistent on lower Slough Creek. That said, all three major streams in the Lamar System see great hatches and also days without fishable numbers of aquatic bugs.

For information on insects and other food sources noted here, visit the Trout Prey page.

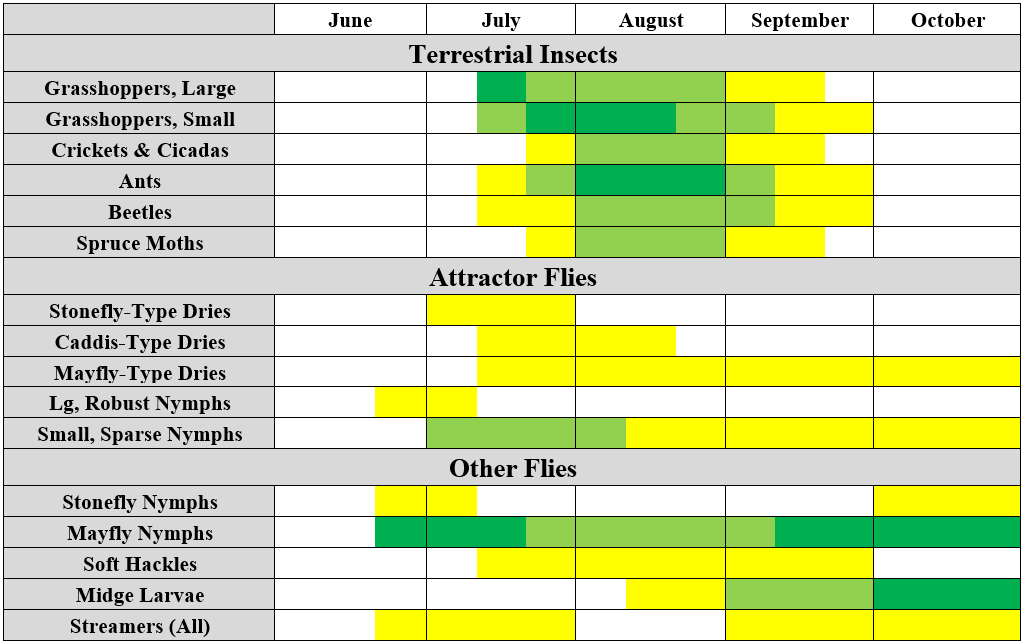

The next table shows other food sources and flies that work well in the Lamar System. In general, flat water calls for smaller flies and more delicate presentations. Only rough water sections of the Lamar and Slough Creek produce well using big “Western-style” attractors such as Chubby Chernobyls and the like.

Top 10 Flies for the Lamar River System

- Bicolor Flying or Parachute Ant, #16–18

- Tan Bob Hopper, #14

- Soda Fountain Parachute, #10–20

- Furimsky’s Gray Foam Drake, #12–14

- PMD Sparkle Dun, #16–18

- March Brown Sparkle Dun, #12–14 (taken as a Tan Drake)

- Upbeat Baetis, #18–20

- Purple Hazy Cripple, #16–20

- Black and Copper Zebra Midge, #18–20

- Beadhead Flashback Pheasant Tail, #16–18

Dave Keltner’s Soda Fountain Parachute imitates all species of Green Drakes as well as BWO, and is useful from #10 all the way to #20.